From engineering execution to enterprise architecture: the Sales domain

In the previous article of this series, we proposed an example of engineering execution on the IT domain. We spent some time detailing the refinement process and the outcomes delivered. We would now like to question how this approach could impact the architecture of a company.

In this article, we examine how we can implement bounded contexts to the architecture of a large company. We ask how it could be relevant to juggle between managing diverse product catalogs, international logistics, omnichannel customer experience and complex performance analytics.

We will explore in particular how omnichannel problems could be solved using this approach, detailing as an example the Sales domain of a luxury company.

An increasing complexity since COVID

With COVID, luxury businesses shifted towards new business models increasing in particular their on-line sales. Companies performance is now heavily dependent on their capacity to integrate new and innovative distribution channels and customer experiences.

● The sales domain spans in-store purchases, e-commerce transactions, and remote personal shopping.

● It must integrate real-time inventory, clienteling tools, and global payment infrastructures.

● Sales events must reflect the brand’s exclusive experiences, limited editions, and regional launch calendars.

● KPIs include revenue, margin, conversion rate, average basket value, repeat customer rate, and cross-sell ratios.

Sales architecture must unify omnichannel data without losing context.The technical challenge of traditional architectures

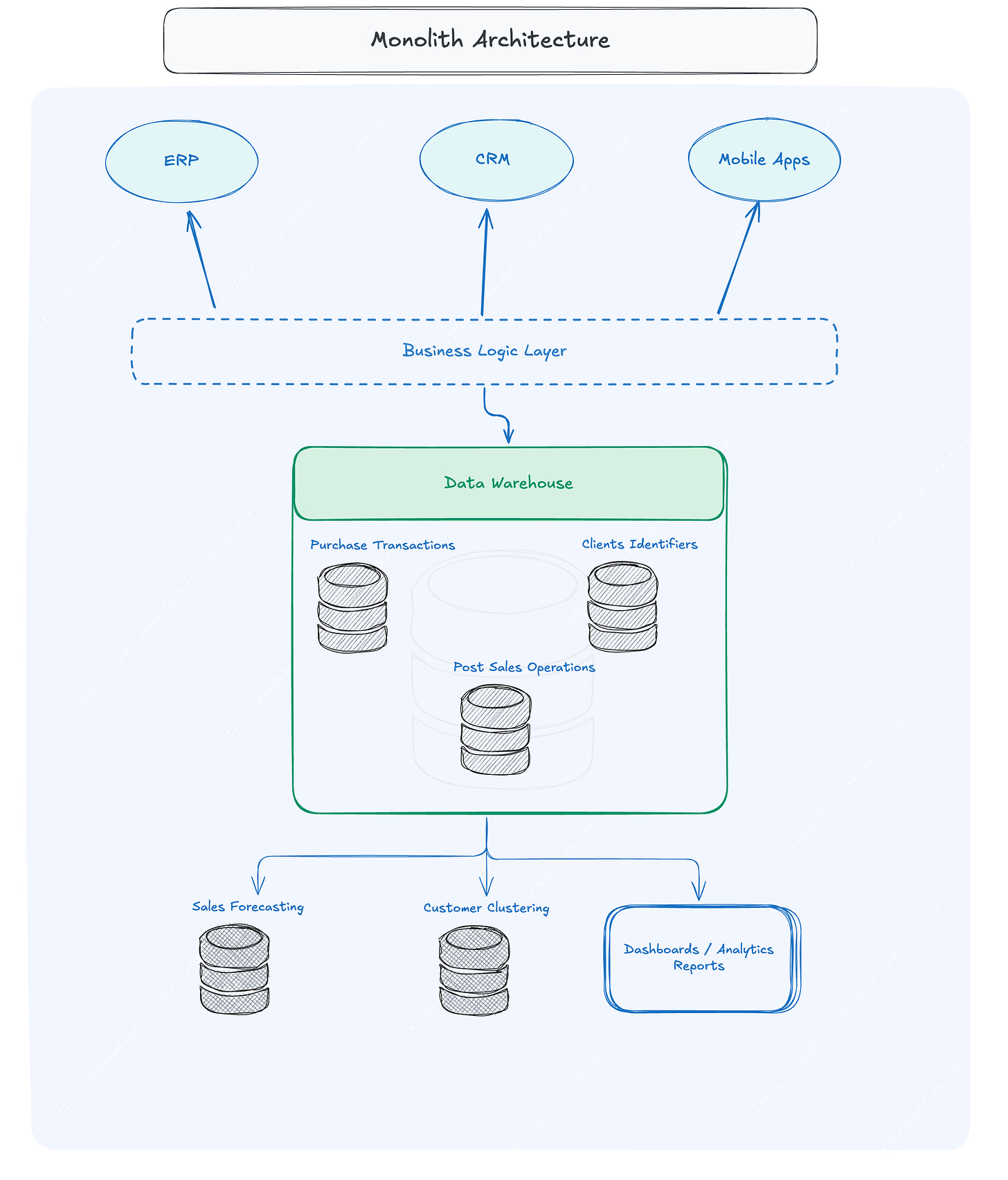

We often observe monolith architectures in large organisations. Data comes from multiple sources (ERP, CRM, POS systems, e-commerce platforms and mobile applications) and converges into a centralised ‘Extract, Transform, Load’ (ETL) process. It feeds a monolithic data warehouse that serves as a single source for all analyses, whether through Business Intelligence tools or Data Science initiatives.

Main sources

The sales domain, for example, aggregates transaction-level data from:

● In-store POS systems across thousands of boutiques globally

● E-commerce platforms with localised checkout flows (e.g., CN, JP, US)

● Mobile-assisted selling tools used by sales advisors

● Clienteling apps managing pre-orders, reservations, and VIP re-engagementsIn this model, all business logic is merged under a single responsibility often managed by a centralised team.

In order to simplify the acquisition and transformation by this single team, the business logic is often harmonised. A single model can be used to acquire data related to transactions and services.

Main entities

Each channel emits structured and unstructured events related to:

● Purchase transactions

● Cancellations

● Promotions & discounts

● Client identifiers

● Payment authorisations

● Post-sale operations (returns, tax refunds, after-sales services)It is worth noting that the Sales domain heavily relies on the data of other domains, current and historical, to improve the capacity of analysis.

This creates both robustness and inflexibility in understanding, maintenance, and evolution. For a company offering multiple services in a decentralized business model, this approach can become problematic when it comes to adapting strategies to local markets.

We can argue that centralised data architectures are optimal when simplicity takes precedence over flexibility. But for an international company with decades of IT history and thousands of product references, this architecture can become a barrier to agility and innovation.

It faces several fundamental challenges:

Excessive Centralisation: A monolithic data model attempting to unify all business concepts, from product technical characteristics to purchasing behaviors of different customer categories.

Loss of Context: Business nuances are diluted during integration. The notion of “available product” can have different meanings for the e-commerce team and the store inventory management team.

Rigid Governance: One model to rule them all, without considering the specificities of different product lines or regional markets.

Growing Technical Debt: Continuous additions without structural redesign, particularly problematic when the company constantly diversifies its offering or enters new markets.

Main problematics

Typical problems faced by the sales domain with this architecture include:

● Product integration delays of several days between creating a new reference and its availability in all systems.

● Frequent inconsistencies between online displayed stock and actual store availability.

● Inability to adapt analyses to the specificities of each product family.

● Complex governance with constant compromises between conflicting needs of different departments.

Let’s discuss how to migrate towards a more flexible organizing principle that can solve these challenges.Let’s discuss how to migrate towards a more flexible organising principle that can solve these challenges, especially in large companies.

Bounded Contexts as an Organising Principle

Operations protect today’s value, investments are bets on improving operations and create tomorrow’s value.

When entrepreneurs think about improving their daily operations, they ask a few simple but telling questions: What is the real pace of the business? How much room do I have to break things and in which areas can I afford it?

Your organisation must be understandable:

What are existing operations, their risks and challenges?

How are these operations supported? Is the support aligned with the need? What are possible investments and what will they bring?

Your organisation must be flexible where adaptability is an advantage, hold firm where stability is non-negotiable, and go deep into detail when precision is critical.

In order to ensure this coherence, reaching a shared vision with your teammates is necessary. Every teammate should understand not only the rhythm of the business, but also the company’s investment priorities. For instance: I’m choosing to invest in customer data, because the risk of GDPR non-compliance is too high. My strategic focus is privacy and the central legal validation of customer lists.

A proposition for omni-canal and complex organisations

In data, using bounded contexts enables questioning the alignment of the data architecture and data governance with the business reality of the organization.

Let’s recall what a bounded context is:

A bounded context is an explicit boundary within which a model (and its associated language) is consistent, unambiguous and autonomous. This boundary is not purely linguistic: it extends to the codebase, databases, team organization, and architecture, but it should not be confused with them.

The notion of bounded context is very useful to help design architectures but is not the only variable used to define an enterprise architecture:

Acceptance of plurality: each bounded context can have its own model adapted to its specific use. Eric Evans highlights that there is no universal perfect model (infoq.com).

Multiple boundary layers: the boundary can be linguistic (terms have only one meaning), physical (code, database), and organisational (one team is responsible).

Pragmatic decomposition: contexts are drawn based on ambiguity in terms, business capability boundaries, team structure, and integration with legacy or external systems. There is no ideal size, only trade-offs that balance clarity, need and maintainability.

Thus, it is distinct from technical architecture: a micro-service may implement a bounded context, but not all bounded contexts must be micro-services (and vice versa).

Let’s take a Sales domain and a term like “performance”. The sales forecasting “performance” is the projected revenue versus the target. The sales incentives “performance” is the number of deals closed per salesperson.

Ideas for potential Bounded Contexts

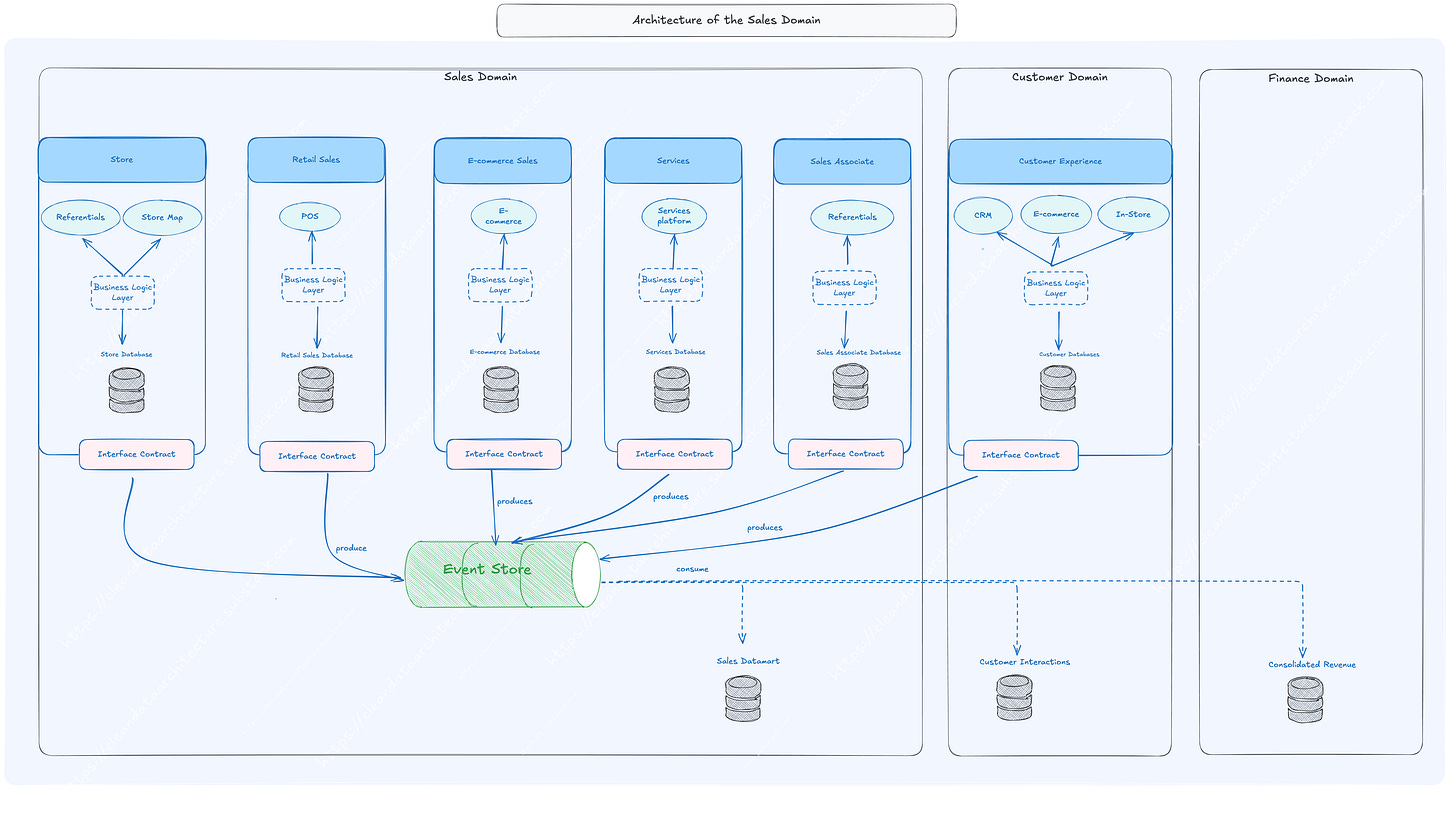

Retail Sales

● Events: Purchase completed, basket abandoned, return initiated.

● Entities: Store, associate, receipt, product SKU, client profile.

● Metrics: In-store conversion rate, upsell ratio, average sale per associate.

E-Commerce Sales

● Events: Cart update, payment authorisation, digital promo usage.

● Entities: Customer session, browser fingerprint, device type, payment gateway.

● Metrics: Page-to-purchase ratio, discount impact, time-to-checkout.

Clienteling

● Events: Wishlist updated, private appointment booked, concierge order placed.

● Entities: Client dossier, associate-client interaction, gift history.

● Metrics: Client lifetime value, retention rate, personalization score.

Revenue for consolidation

● Pulls events from each context to compute financial aggregates.

● Ensures compliance with global accounting standards (IFRS, GAAP).

● Handles cross-context disambiguation for terms like “sale”, “refund”, “net revenue”.The advantages of an alignment with Business Organization

People often work in silos, convinced they are speaking clearly, yet they rarely invest in building a truly shared language. A company is an organisation cohabiting very different roles, responsibilities, locations, and habits, and they forget that each specificity pulls the language in very different directions. Accounting, for example, is codified and standardised through formal and local education, leaving little room for ambiguity in a specific country. In contrast, fields like technology or governance are mostly learned through practice, where rules are fluid and vocabulary evolves over time.

Actively constructing bounded contexts creates shared understanding across functions and activities. The alignment begins with content, the language, the models, their specificities and extends to strategy. It may sound obvious, but in large organizations with cross-functional activities, when people around the same context don’t speak to each other, dependencies go unnoticed and strategy collapses in the gaps.

To summarize, shared business knowledge and aligned functional responsibilities enable the strategy to happen.

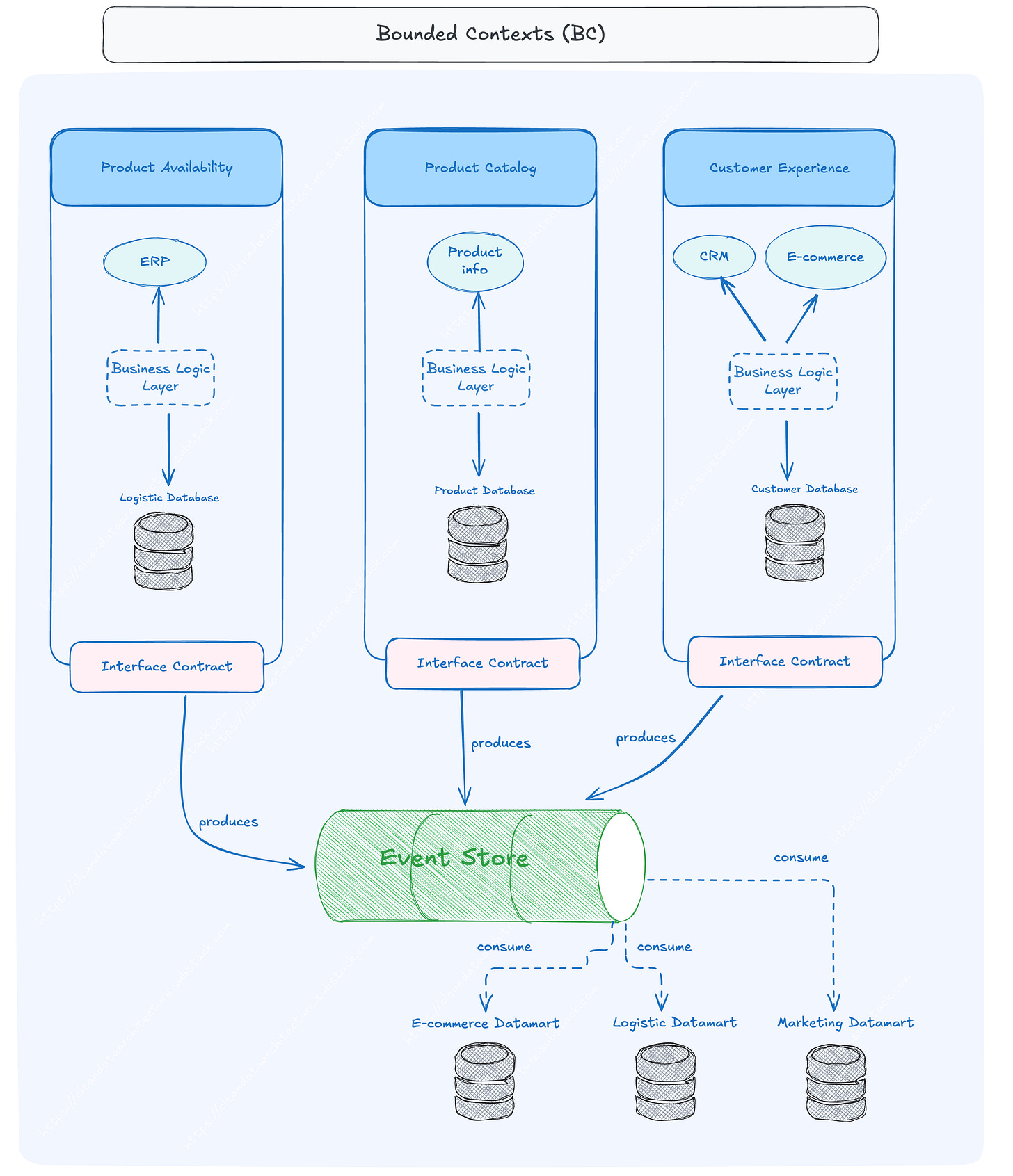

Data Architecture guided by Bounded Contexts

When we try to explain bounded contexts in an organisation, we often refer to the concept of Data Domains.

The Data Domain is the organisational unit that will have the governing responsibilities of all the bounded contexts relating to this functional concept.

Supply:

This domain manages the movement, storage, and availability of products across the entire supply chain. It has its own data model optimized for tracking inventory levels, stock locations, replenishment needs, and product availability in stores and warehouses. Source data comes from warehouse management systems, inventory tracking tools, supplier shipments, and in-store stock systems.

Product Availability: This bounded context focuses on product availability, with a model allowing fine-grained inventory management by store, inter-store transfers, and replenishment forecasting. The team includes supply chain and inventory management experts.Product:

This domain focuses on the complete product lifecycle, from conception to sale. Its data model is optimised for managing technical characteristics, variants (size, color), manufacturing processes, costs, and material composition. Source data comes from PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) systems, design tools, and quality management systems.

Product Catalog: This bounded context becomes responsible for all product-related information. Its model is specialised to reflect the specificities of each category, with adapted attributes (resistance for technical equipment, performance for specialised items, etc.). The responsible team includes product managers specialised by product category.Customer:

This domain focuses on customers, their preferences, purchase histories, and interactions with the brand. Its model is optimized to support personalization, loyalty, and customer service strategies. Data comes from CRM, loyalty programs, satisfaction surveys, and social media interactions.

Customer Experience: This bounded context manages everything related to customers and their interactions with the brand, with a model optimised to track cross-channel purchase journey, preferences, and customer lifecycle. The responsible team includes CRM and loyalty experts.In addition to these domain definitions, the company needs to design an integration layer, with a “Context Mapper,” that plays a crucial role in enabling cross-domain analyses. For example, to analyze the performance of a new product range, the Context Mapper will combine product data (technical characteristics), sales data (volumes by region), and customer data (buyer profiles) in a coherent manner.

From a platform perspective, this “Context Mapper” requires a single “way of speaking” (metadata management). From a governance perspective, the governance of this cross-domain layer can be delegated to certain Data Domains.

These bounded contexts publish their business events to a central event store, which then feeds specialised data marts. The governance of the data marts are themselves delegated to a certain Data Domain.

This architecture brings several advantages for an international multi-product company:

Local Coherence: Each bounded context maintains its own internal coherence. For example, the product team can use technical vocabulary specific to each category without creating confusion in other domains.

Autonomy: Teams can evolve independently. The team responsible for the Customers bounded context can enrich its data model with new behavioral analysis dimensions without impacting product management or sales systems.

Semantic Clarity: Business terms retain their precise meaning in each context. The term “performance” keeps its specific meaning whether used by the product design team (technical characteristics), the marketing team (attractiveness), or the sales team (sales results).

Evolutivity: Changes are contained within their respective contexts. The introduction of a new product category in the company’s offering can be managed primarily in the Products bounded context, with clear interfaces to other domains.

Architecture of the Sales domain

Now let’s focus on the sales domains and its interactions with other domains:

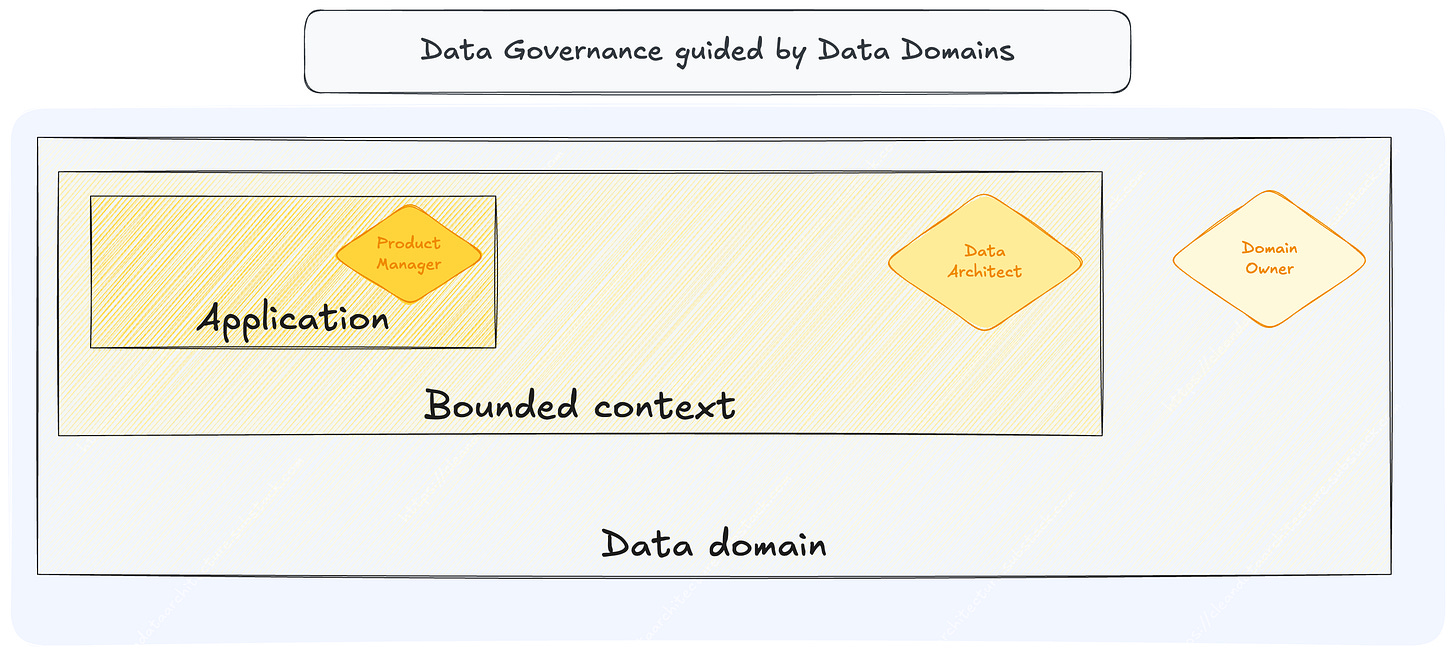

Data Governance guided by Data Domains

Data domains are a sum of bounded contexts that relate together functionally and can be governed by the same functionally responsible team. If your domains are well constructed, governance teams should be able to relate to all bounded contexts manipulated by the domain.

Each data domain has its own governance structure:

The Domain Owner is responsible for the strategic direction of the domain.

The Governance team can be composed of data stewards and owners or any other teammate that makes sense for the complexity of the organization. From experience, a simpler governance team is preferable.

Governance for the Sales domain

● Owner: Sales Director or Chief Commercial Officer

● Stewards: Sales Operation Managers, Retail Managers, Store Managers

● Lead: can be reporting centrally to a governance office, supports owner in their strategic design and stewards in their literacy and operationsData architects ensure the coherence of one or several bounded contexts depending on the complexity of the context. He can be in charge of unifying the visions of several Product and Data Product Managers and the coherence of the implementation.

Product managers and data product managers ensure the operational governance of their products.

In this context, the governance office and platform should offer a single vision on how to communicate together between applications (data contracts), between bounded contexts (architecture decisions) and between data domains (executive committees). They should also provide advisory and literacy both on the vision and the operationalisation, an enabling and after-care service.

Refactoring a Data Warehouse by Data Domains

For a company with a legacy of data systems and a wide range of products, the transformation towards a domain-driven architecture cannot happen overnight.

The data warehouse is often the place where the lack of clear bounded context is the most problematic.

As an end-user, when I look at the data available, how can I make sure that the “performance indicators” that I use really mean what I want and come from the right source?

We argue that any source acquired and any transformation created without a clear bounded context in mind is a functional debt that will need to be repaid tomorrow.

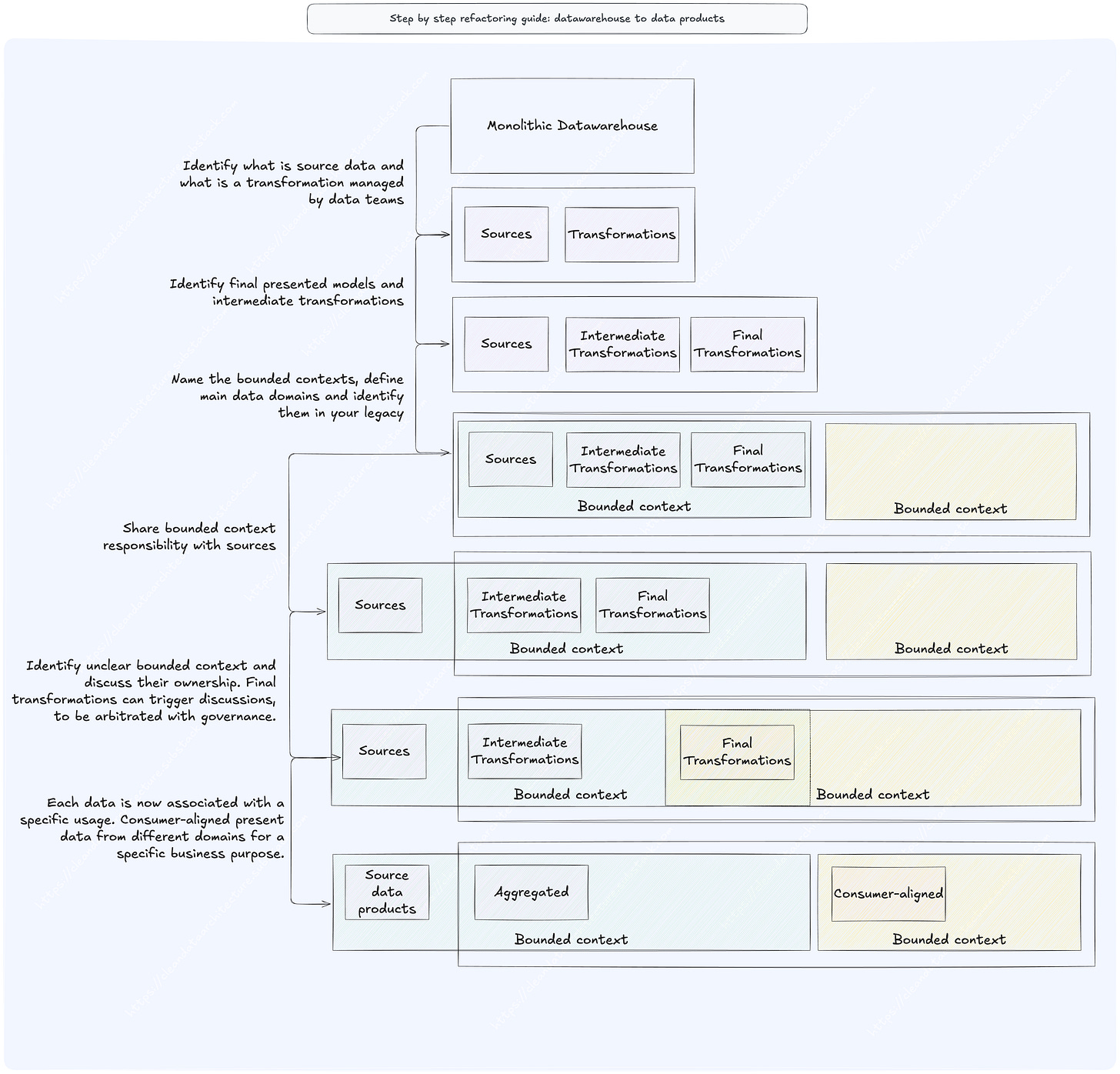

Here’s a progressive approach to refactoring an existing data warehouse:

Each step brings identifiable value and can be measured over time. It also allows a progressive transformation, domain by domain, perhaps starting with domains responding to a strategic company orientation like a unified product catalog or an omnichannel customer experience.

Measuring Success

How do you know if your implementation of Bounded Contexts in your Data Architecture is successful? Here are key indicators to track, with a focus on financial and operational outcomes:

Faster incident resolution: Measure the decrease in issues caused by misunderstandings of business terms. Fewer incidents mean less time spent fixing errors, which directly saves operational costs.

Shorter time-to-market for data products: Track how quickly analytical solutions and updates can be delivered. Faster insights allow for quicker pricing adjustments, promotion planning, and inventory decisions, impacting revenue.

Fewer unsolvable cross-domain dependencies: Clear, co-created roadmaps reduce blockers and project delays, which lowers project costs and avoids lost sales opportunities.

Better data quality: Monitor completeness, consistency, and accuracy of domain data. High-quality product, customer, and sales data leads to more reliable forecasts, optimised stock levels, and reduced write-offs.

Higher user satisfaction: Measure how much business users trust and rely on the data products. Confident decision-making supports revenue growth and reduces costly mistakes.

Agility in response to business changes: Track how quickly the architecture can support new product launches, market entries, or pricing adjustments without major redesigns. Faster adaptation protects margins and captures new revenue streams.

Reduced operational and financial risk: Clear responsibilities and domain ownership lower the chance of costly errors or compliance issues.

For a global company with a diverse product portfolio, success also translates into the ability to personalise offerings by market while maintaining overall brand coherence, data consistency, and financial control.

Conclusion

Implementing bounded contexts in your data architecture is a transformational journey, not just a technical migration. For an international company with a diverse product offering, this approach provides a structuring framework that aligns technology with business reality.

This journey touches on culture as much as technique. It requires a mindset change, moving from a centralised and monolithic vision of data to a distributed and contextualised approach. It also involves redefining responsibilities, where each business domain truly becomes owner of its data.

The benefits are substantial and multiple:

Coherence: data faithfully reflects the nuances of each product domain

Clarity: business terms retain their precise meaning in each context

Autonomy: teams can evolve at their own pace, adapting their models to the specificities of their product category or function

Adaptability: the architecture can organically adapt to company expansion, whether it’s new products, new markets, or new channels

For a company leading in its field, adopting DDD in your data architecture is a strategic lever to maintain your agility and leadership, and is even more powerful if you are already planning to make major changes into your infrastructure.

Dare I say that architecture is another way to do politics 🤭 Just joking ! Thank you 🥰

Excellent article which is a golden mine of solutions for the future.

There is an architectural key here under the "event store" cited in the article, it is the "event sourcing" design. Event sourcing is a way to store events and not raw data. Because you can recreate the data from events but cannot recreate events from data.

We have the technology to design event sourcing architectures since roughly 10 years. But there are 2 blockers for that: the lack of compatible business design, which can be solved with DDD and its bounded contexts approaches. And the mindset shift: we are losing lots of architecture departments when referring to sourcing events instead of data. But the mathematical tools allow us to manage events, when stored according to the identified bounded contexts, very quickly and with a precision that storing raw data cannot provide. An event "PurchasedCompleted" weights much more precise information than "the raw data itself resulting from the purchase".

What about performance and ecology of actions? That's where the CQRS architectural pattern comes in: separation of concerns between an acceptable "slow" database of writing events, and a hugely fast database of normalized (for the bounded context) data, which is read-only, and very fast. What's interesting here, is that the reading database (the production) is throwable. A bug? The reading database can always be recreated from the event database.

But for that, a huge mindset shift is mandatory to change from traditional architecture.